Latest Articles

WhatsApp Cool Customizable Video Call Avatar Beta Testing Started

Whatsapp is quietly developing a cool feature that will allow users to make video calls without showing their faces. Instead, they’ll be able to…

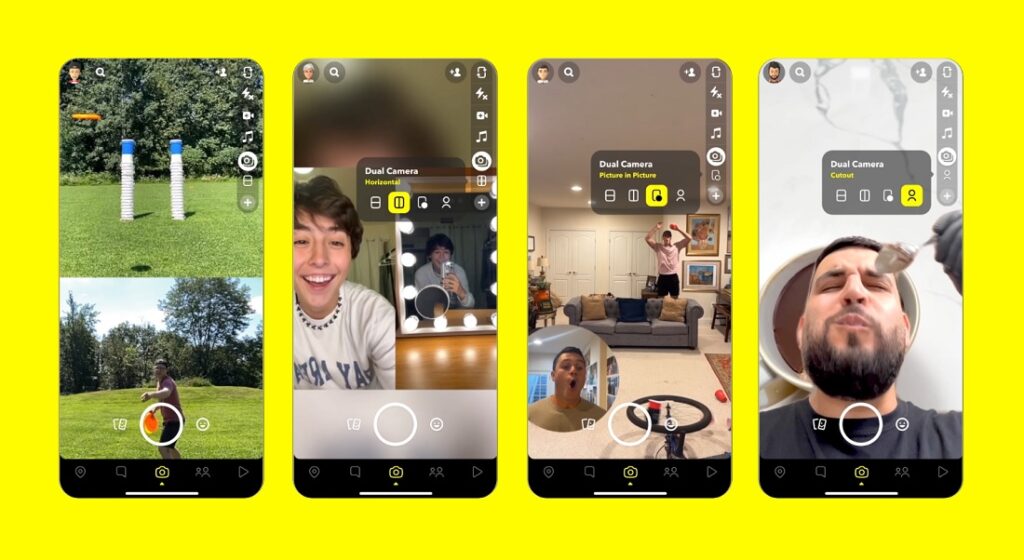

Snapchat Introduced BeReal Moment Dual Camera To Enhance User Experience

Popular social media platform Snapchat has announced a new addition to its main camera features: a Dual Camera. Snapchat Users can now simultaneously capture…

Amazon To Back TikTok’s Book Club Likely To Diffuse Gen Z TikTokers Boycott

Recently, Amazon has decided to support TikTok’s Book Club, a collaborative initiative to promote the habit of reading books. TikTok Book Club is a…

Twitter Testing “Co-Tweet” Allows Posting In Followers Profile

Once again, Twitter is finalizing a great update that could be of huge benefit to everyone. The social media company announced this significant development…

Recent Hiring Hints ‘Netflix’ Is Taking Steps Toward Cloud Gaming

Netflix, the most popular streaming platform, recently revealed its cloud gaming plans to the world. The current job listings suggest that it is targeting…

WhatsApp Now Supports 512 Members Group And 2 GBP Files

The latest update of WhatsApp allows each user to create a group double the size of the earlier versions. In what is regarded as…

Asus Laptops Vs Apple Macbook: Which Is Better Brand? Find!

Asus and Apple are two leading brands in the laptop segment. If asked to choose one, which laptop brand would you prefer – Asus…

ChromeOS Video Calling To Receive Major Upgrades Such As Built-In Video Effects

After improving the background blur in Google Meet web clients, Google has turned its attention to revamping the video calling experience in Chromebooks. Google…

Raspberry Pi Latest Update Adds Searchable Main Menu, Picamera2 Support & More

The UK-based educational charity organization Raspberry Pi foundation has unveiled a reworked Operating System to upgrade the look and feel of several significant areas…

Guilded Added Features For Shallow And Deep Search & Tracking Events

Roblox Corporation-owned VoIP, instant messaging, and digital distribution platform Guilded released new updates with more features this fall. The new features are intended to…

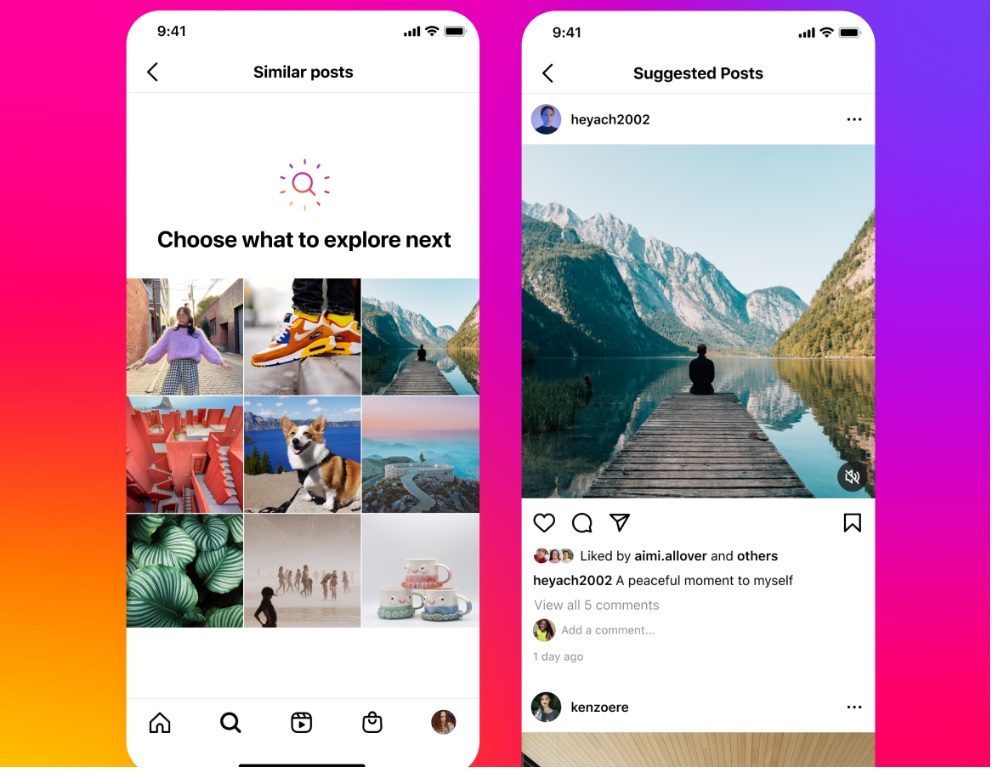

Teens Are Moving Off From Facebook And TikTok Is Racing For The Top

A recent Pew survey suggests that US teens choose TikTok over Facebook as their preferred social media platform en masse. While Instagram and Snapchat…

LinkedIn Experiencing A Problematic Surge In AI Based Fake Profiles

LinkedIn, the popular business and employment-oriented online service platform is experiencing a problematic surge in the number of fake profiles and phony identities. According…

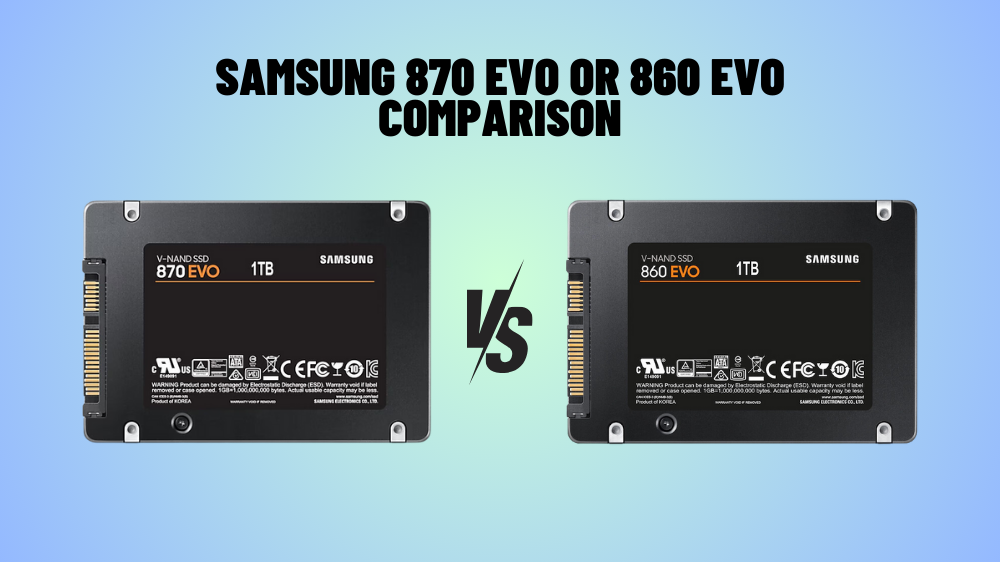

Samsung 870 Evo Vs 860 Evo SSD Comparison 2024 : Know Features!

A solid-state drive, also called an SSD, is a sort of storage device utilized in computers or laptops. A good storage device even helps…

10 Top Data Storage Applications

There are so many data storage applications out there that whittling down the list to a handful was quite a challenge. In fact, it…

Data Storage Industry Braces For AI And Machine Learning

You hear a lot these days about artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. Magazine article and TV news spots drool over the transformational potential…

Top Tips For Object Storage : Predict And Analyze Storage Needs

The first article in this series covered what Object Storage was and provided an overview of some of the vendors and their products. Now…

POPULAR

No posts

No posts