We are at a significant crossroads in the world of file management. The historical approaches to managing the growth, cost and complexity of unstructured file-based information have started to hit a wall across enterprise environments of all sizes.

In a June 2006 Taneja Group survey of global IT decision makers, we found that 62% of respondents now identify “file management” as either “the top priority” or “one of their top priorities” requiring immediate attention in their data centers. This statistic is further confirmed for us daily as we talk with end users evaluating a wide range of new technologies to improve their file management approaches. Some of the most common new technologies that impact file management include:

Wide area file services (WAFS)

WAN optimization and application acceleration

Distributed and clustered file systems

- Network file management (NFM)/file virtualization

- File/document management software

- File classification software

- File data placement/movement controls

Note that the vast majority of these technology categories were not even mature 36 months ago. So, what accounts for this concerted focus and innovation around the management and control of files?

Quite simply, what has changed is the relative criticality of file data as it relates to mission-critical business processes. At some point in the past three years, we collectively crossed a threshold wherein file data became the communicative lifeblood of every company in the world. Nearly all workflows ultimately run through some manner of file infrastructure, increasingly spanning multiple geographies, business partners and IT infrastructures, all with real-time performance and access requirements. That simple transformative fact explains file growth, its complexity, and vendors? innovation explosion in reaction to this state of affairs.

IT déjà vu

This is not a historically unprecedented event, however. We have all seen this movie before. Exactly 10 years ago, we saw the block storage world going through a similar shift as open systems amplified the ease with which storage resources could be utilized and shared across core business processes. Storage managers at that time were tearing their hair out trying to control basic growth, cost and complexity issues. Of course, the evolutionary breakthrough that transpired was the birth of the storage area network (SAN).

At the highest level, the SAN transformation of the 1990s represented an explicit agreement by users and vendors to pursue a common architectural approach for deploying and sharing storage resources. The extension of the shared resources concept inherent in the “area network” framework opened up an entirely new dimension for the storage industry.

By analogy, we are now at a similar inflection point with regards to enterprise file management. In short, we are now ready to rationalize our collective approach to managing file data by once again abstracting and extending the “area network” concept to another layer of the infrastructure. We are now ready to begin building file area networks, or FANs.

The Birth Of The FAN

A FAN is a systematic approach to organizing the multitude of file-related technologies existing in today’s enterprise. The goal of a FAN is to provide enterprises with a scalable, flexible and intelligent platform for the cost-effective delivery of enterprise file information. An appropriately architected FAN will provide an enterprise with previously impossible levels of file control and economic returns. Some of the capabilities that define a FAN include the following:

- Enterprise-wide, pervasive controls of all file information, and management of file attributes based on metadata and content values, regardless of platform.

- Ability to establish user file visibility and access rights based on business values (e.g. departments, projects, geographies) regardless of physical device residency.

- Non-disruptive, transparent movement of file information across all geographical boundaries rendered obsolete.

- Creation of file management services that are deployed as true “services” to the entire infrastructure, not deployed in application-specific silos.

- Measurable ROI for file management due to consolidation of redundant file resources (e.g. de-duplication of redundant files).

Do these capabilities sound vaguely familiar in their scope and impact? If so, it is because the FAN is to traditional file management what the SAN was to direct-attached storage: A massive step-function up in capabilities, control, and ROI.

As with a SAN, there are myriad technologies and approaches that will be possible in the architecture and deployment of a FAN. Many vendors will participate in the FAN ecology, and innovation in FAN solutions will continue at a fast pace over the next several years. Establishing an accepted definition of the FAN is critical because it will allow IT teams to develop common shorthand and reference models for how they architect, deploy, manage and augment their file infrastructures. In the absence of this kind of framework, many enterprises will simply drown in coming years, not only from a deluge of mismanaged file data, but from the inevitable vendor confusion that would result without a common nomenclature. To that end, let’s turn now to what actually goes into a FAN:

Elements Of A FAN

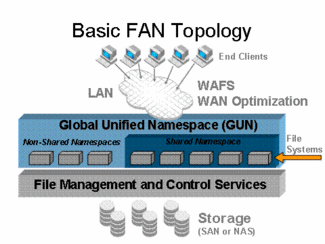

There are six core elements that will comprise any enterprise FAN. They can be itemized as follows [see Diagram].

1. Storage devices. The foundational level on top of which a FAN resides is the storage infrastructure. This can be either a SAN or a NAS environment. The only pre-requisite is that a FAN must leverage a networked storage environment to enable data and resource sharing.

2. File serving devices/interfaces. Either as a directly integrated part of the storage infrastructure (e.g., NAS), or as a gateway interface (e.g., SAN), all FANs must have devices capable of surfacing file-level information in the form of standard protocols such as CIFS or NFS.

3. Namespaces. All FANs are premised on the existence of file systems with the ability to organize, present and store file content for their authorized end clients. This capability is referred to as the file system’s “namespace.” It is one of the central concepts around which the entire FAN must revolve. As we will explore, there are several kinds of namespaces possible in a FAN.

4. File management and control services. The other central concept in the architecture of a FAN is the software intelligence that inter-operates with namespaces to create new value across the entire enterprise. From a deployment perspective, these services might be integrated directly with file systems, or in networking devices, but they may also be stand-alone services. Examples include file virtualization, classification, de-duplication, and wide-area file services. We will explore these capabilities in more detail below.

5. End clients. All FANs have end client machines that access the namespaces created by file systems. These clients could be on any platform or computing device.

6. Connectivity. There are many possible ways that a FAN connects its end clients to the namespaces. They are commonly connected across a standard LAN, but they may simultaneously or alternatively leverage any manner of wide-area technologies, as well.

Namespaces: Fabric Of The FAN

The June 2006 Taneja Group study also found that over 57% of global IT users either already have deployed or are currently exploring deployment of advanced namespace technologies to improve file management. In other words, those users are assembling their first FAN, whether they realize it or not. Understanding precisely what a namespace technology means to a FAN is therefore critical. In fact, by analogy, we can say that the namespace is to the FAN what the switching fabric is to a SAN. However, the key difference with a FAN is that we are talking about relationships of information presentation and not about physical device relationships.

The presentation, access, and general organization (i.e., the directory structure) of any given file system’s data is referred to as its namespace. For any FAN, there are only three kinds of FAN namespaces possible under any circumstance. In coming years, most enterprises will have a combination of these three [see diagram above] deployed in combination to address various issues.

1. Non-shared namespace. This is the default when enterprises establish basic file services or traditional NAS. It is a user-level presentation of information corresponding to a file system image that is married to a given physical machine. In other words, there is no sharing of information across multiple file system images. The vast majority of file systems deployed today deliver non-shared namespaces. They have been the workhorse of smaller deployments. However, they are the source of many IT headaches as they grow and outstrip their file system capabilities.

2. Shared namespace. This is when a subset of an enterprise’s physical file presentation environment has been federated so that information can be shared across multiple homogeneous machines. This enables the IT team to use those homogeneous machines for a common presentation of user-level information to designated end clients. Typically, shared namespaces are platform specific and not intended for deployment across all end clients in the enterprise. Because they tightly couple multiple file systems, shared namespaces can resolve significant file visibility, collaboration and performance issues for a targeted subset of the enterprise. Common examples include clustered NAS environments and clustered or distributed file system deployments.

3. Global unified namespace (GUN).The Holy Grail for namespaces in the FAN is what Taneja Group refers to as a GUN: a truly heterogeneous, enterprise-wide abstraction of all file-level information, open to dynamic customization based on administrator-defined parameters. This is the level at which significant management control and leverage is finally possible. A range of software intelligence can then be applied to the GUN with assurance that it will be applicable across the entire enterprise (e.g., access controls, file virtualization, classification schema, de-duplication, etc.). From an architectural perspective, a GUN could be established in any number of ways, including distributed host-based software or network-resident approaches.

Control And Manage The FAN: Software Services

The other major definition to explore with a FAN is the element of file management and control services. These are the software tools that interact with the namespaces, physical file systems, storage, and connectivity—all in order to add significant value to the FAN. These software capabilities are the brains of the FAN, and they encompass a range of existing technologies as well as new innovations recently hitting the market.

If we continue with our SAN analogy, we can say that these software services are to the FAN what storage management software is to the SAN. A brief tour of these software services should include the following product categories:

- Migration services. Moving files non-disruptively underneath shared namespaces or Global Unified Namespaces is one of the most powerful IT-level benefits of a FAN. In fact, this is part of the core “plumbing” of the FAN. This capability can be achieved at many levels, including distributed host-based software, network-based, or appliance-based approaches.

- Replication services. All files in a FAN must be able to be non-disruptively replicated between resources and geographies. This may take place through any number of technologies deployed at various layers of the infrastructure (e.g., host, NAS appliance, or network). Support for non-disruptive file-level replication is critical for any FAN architecture.

- Placement services.The ability to place file-level data on a given physical device based on its attributes will be a key component of a FAN. Optimal data placement ensures that the servers and storage supporting a FAN are maintaining appropriate performance and utilization levels. This can be achieved through a range of in-band network-resident approaches such as network file management (NFM) devices, some information classification and management (ICM) technologies, or through distributed software approaches.

- Access continuity services. Once a namespace is established with a FAN, it is critical that the end users maintain non-disruptive access to that abstracted file-level information. In the event of site failure or device failures, there most be some manner of complete fail-over and availability to ensure that a persistent presentation of data is maintained across geographies. This can be achieved through many kinds of file replication tools and wide-area tools, such as WAFS appliances, that work in tight coordination with application fail-over and recovery.

- Information classification services.The information classification and management (ICM) category has gained significant momentum in the past 24 months as enterprises are learning to execute granular control on files. This software enables content-level indexing of all information that then supports policy-based controls, access, and retention. ICM is an essential component of any FAN.

- FAN extension services.Being able to extend access to the FAN across geographies is critical for most enterprises. As a result, a FAN must be able to support wide-area connectivity into its namespaces. The goal is not merely to connect geographies, but to connect them with near-LAN access speeds and service levels. Various technologies can accomplish this for the FAN, including various WAN optimization technologies and WAFS.

FAN Leaders

Now that we have a basic definition of the FAN, we can turn to the vendors that are supplying the technologies that enable FAN functionality. In this article, we will highlight a few of the tier one vendors that will be providing the overall FAN framework to end users, either directly or through OEMs and partners. These companies already have the wider views on what constitutes a FAN. Clearly, as this market definition gains traction, both the roster of competitors and their range of capabilities will expand significantly. (Vendors are listed in alphabetical order).

- Brocade. Brocade has made a clear strategic shift to also address file-level management issues in recent years, expanding beyond block-level SAN fabric switching. With its acquisition of NuView and that company’s various namespace creation and file services capabilities, as well as its Packeteer-Tacit partnership, Brocade is positioned to drive FAN solutions as a distinct opportunity still aligned with its core SAN switching business. This could prove to be a highly differentiating strategic move for Brocade in coming years.

- EMC. EMC has committed a significant amount of energy to establishing a FAN strategy. With the acquisitions of Documentum and Rainfinity, EMC now has a powerful range of file management software services, as well as a namespace creation and management capabilities. Expect to see EMC drive into additional file services in coming quarters as their strategy unfolds.

- Hewlett-Packard. Microsoft’s largest OEM partner, HP has enjoyed a strong market presence in NAS for several years. The company has internally developed file-level ILM capabilities (classification, migration, de-duplication) well suited to support a range of FAN software services, as well as OEM relationships with players such as PolyServe (Linux and Windows-based clustered file systems) and Riverbed (WAN optimization) that fit well into a FAN portfolio. We expect to see HP play a large role in FAN adoption because of these factors.

- Microsoft. As the owner of the most pervasive server platform, Microsoft has the opportunity to both position and shape the growth of FANs. In addition to namespace technologies such as DFS, the latest Windows Server R2 release provides a full suite of software services that can have an impact on the quality of control customers will be able to execute on a Microsoft-centric FAN. For the simple reason that most FANs will be built on Microsoft technology, they should provide leadership.

- Network Appliance. The pioneer of the enterprise NAS market has already made significant investments to prepare for the emergence of the FAN, as well. NetApp’s new GX cluster-based platform will ultimately enable advanced namespaces, and the company has a range of both internally developed and partnered technologies for FAN software services, including migration, replication, classification, and de-duplication.

This is the very beginning of the FAN era, so rapid innovation and proliferation of technologies should be expected. However, in 2006 and into early 2007, expect to see these vendors play a defining role by extending the capabilities of enterprise file management through its next evolutionary stage: The File Area Network.

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/